This issue covers several scary bridges, all in the area of the former Transandine Railway, El Ferrocarril Transandino. It also covers other parts of the former railway.

The Transandine Railway traveled from the town of Los Andes, Chile, 248km over the Andes mountains to Mendoza, Argentina. Construction started in 1887 and finished in 1910. The Los Andes rail head has an elevation of 813m, the summit tunnel is at 3176m, and the Mendoza rail head is at 767m. To overcome the steep grades and sharp curves involved a narrow gauge (1 meter) cog railroad was used. Originally only steam locomotives were used, but they were later replaced with electric and diesel locomotives.

When first constructed the Transandine Railway was a major improvement to the alternatives: crossing the Andes by horse, or taking a steam ship around the southern tip of South America. However, due to the incredibly rugged terrain the cost of operating the railroad was very high; it was never a financial success. In 1984 an avavalanche severely damaged the road. The damage was too costly to repair without government aide, of which was declined.

Today there is a very windy two lane highway following about the same route, and the majority of the Transandine Railroad is abandoned. A small section is still in operation to carry copper solution from a mine to a refinery in Los Andes.

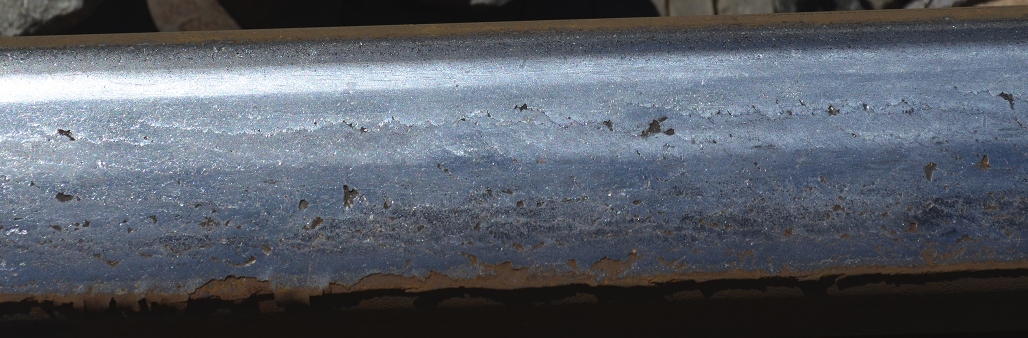

There has been ongoing discussion of reopening the Transandine Railroad. One idea is to restore the old meter gauge cog railway using the old route. This would require restoring the bridges and tunnels, clearing & stabilizing the grade, constructing numerous snowsheds, and providing avalanche protection. Some people have suggested this can be done easily, but following pictures might disabuse them of that notion.

Another plan calls for building an all new railroad using broad gauge track (to match other South American railroads). This would involve a new grade on a somewhat simmilar route, lower maximum elevation, and a substantially longer summit tunnel. The longer tunnel would be costly to construct. But it would provide faster and higher capacity service, reduce the avalanche danger, maintenance cost, and overall track length. The longer tunnel would also avoide the stretches of track that have been undermined by landslides.

As of September 2012 (when these pictures were taken) there was no sign of new construction. Information on future railroad plans was difficult to find, and I am not optimistic. One Chilean summed up the question of a new or reopened Transandine Railroad as "It would be nice. But it will never happen because it requires too much cooperation from Argentina." I hope that he is proven wrong.

This area be found on Google Maps. The old railroad follows Route 60. In addition, if you can find a copy, El Ferrocarril Trasandino has numerous pictures from the operation and construction of the railroad. And, if you can read Spanish, it also has a lot of history.

These photos were all taken on the Chilean side of the railroad. As origionally constructed, this 89km side of the road included 4.2km of retaining walls, 270,000 cubic meters of rock & earth moved, 6,000 tones of steel, 23 bridges with a total length of 264.7 meters, 6 kilometers of tunnels and snowsheds, 3 stations, 3 stops, and 2 rail yards [1].